VENTOTENE

Location and Topography

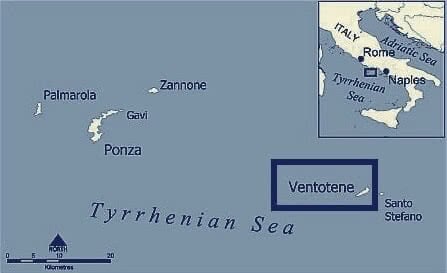

Ventotene is located in the Gulf of Gaeta and belongs to the Pontine Arcipelago, a complex of small volcanic islands in the central Tyrrhenian Sea. In Italian, the name ”Ventotene” denotes an island that has wind (vento = wind),”il vento insoma” (the windy sign).

Ventotene can be reached from the Italian mainland and, depending on the ferry timetables, from Ponza. On the mainland, the main port for the islands is Formia (approximately two hours by ferry, one hour by catamaran), with seasonal connections from Naples and other ports. In the summer, there are also occasional ferries connecting Ventotene with the island of Ischia. Tickets can be bought at a kiosk by the port in Ventotene.

Exile History

Exile on Lipari was seen in two phases. The first being the Roman Imperial period and the second, under Italy's 20th century fascist dictatorship. In the early Roman Empire, it is argued that Ventotene, known as Pandateria in ancient times, was a catalyst for the imperial period's use of islands as places of exile. In 2 BCE Augustus banished his daughter Julia to Pandateria on adulterous grounds. Members of the Roman imperial house were often banished to small islands; for example, Tiberius banished Agrippina the Elder to Pandateria, Claudias banished his niece to Pandateria and, Nero banished Octavia to Pandateria.

The Middle ages saw little known activity on Ventotene. An ex-prisoner, Alberto Jacometti, describes this period with foliage overgrowing, its only purpose to shelter pirates who brought back its historic mission and built on the rocks prisons where in Ventotene ”you sent a chain of freed convicts, with the charge of cleaning from the bush and making stripe

In the twentieth century, on 5th November 1926, Fascist Italy tightened its hold on citizen freedom and once again political exile, or confino politico, was practiced in Italy. Some days later, Arturo Bocchini, the newly appointed head of police, set out to locate places of exile for political deportees, particularly focusing on barely inhabited islands, one of which was Ventotene. An interesting consequence of forcing socialists, anarchists, liberals and communists to live together was that the Fascists created ample conditions for the spread and development of ideas that the regime opposed, a phenomenon which wildly spread throughout Ventotene.

Figures of Note

Ventotene is an island known for its political intellectualism and developments. Figures on this island were key players in the long-term rejection of Italian Fascism. The fight against Fascism was not repressed, but rather continued to be fought right on the grounds that demanded it to be silenced. While Italy faced Fascism, Ventotene grew the seed of democracy that eventually fed the future Italian Republic and its constitution.

Prisoners devoted themselves to the educational programs on the island which spanned from basic levels through to intermediate and then reaching the highest theoretical production, with these places often being called ”prison universities”. While confined, deportees were known to remember their stay as a veritable university courses in opposition and as an academy of resistance. Such exile islands became spaces of communication, fertile ground for new coalitions and contact zones where deportees of different geographical, political and class origins became acquainted with one another and where new political ideas were developed. Communist leader and prisoner Luigi Longo stated that Ventotene was ”a center for political formation of the confined and of organisation for peace and freedom within the country.

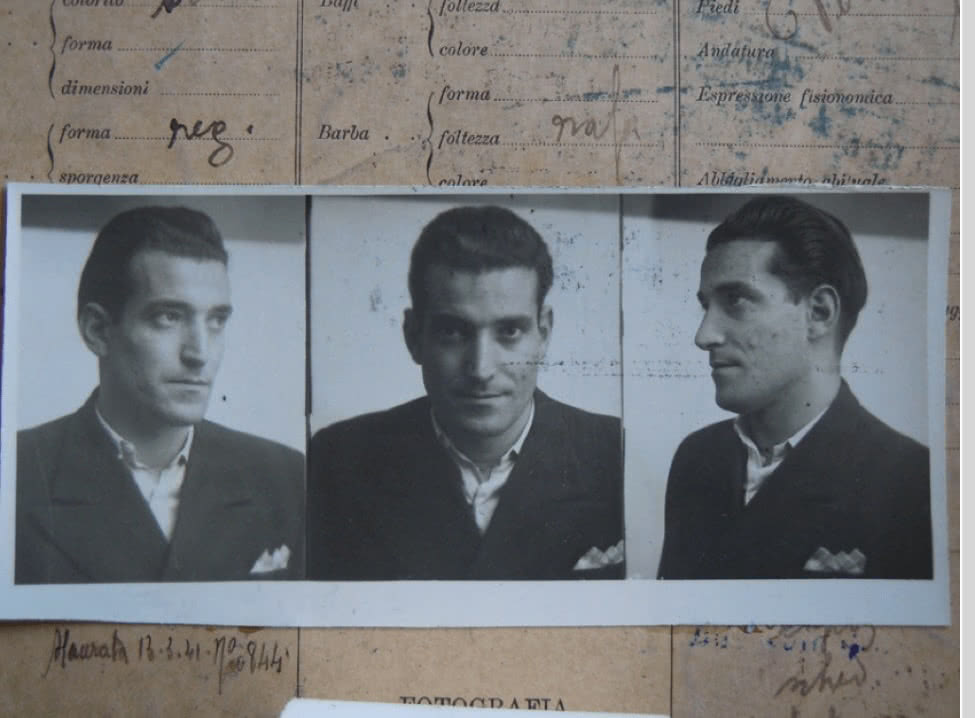

Key individual figures exiled on the island included Alberto Jacometti – an anti-fascist arrested in November 1940 by the Gestapo and later in December was taken on a truck with other prisoners to Ventotene for exile. Jacometti wrote the book "Ventotene" which contains detailed descriptions of his life as an exile.

Other key figures include Ernesto Rossi and Altiero Spinelli who wrote The Ventotene Manifesto – a prominent piece of work that was born and developed in exile while presenting the views of the antiestablishment. The work is considered an innovative piece and has remained the theoretical basis for many of the claims still made by federalist thinkers in Italy and across. In June 1924, Rossi strongly opposed the Fascist regime and decided to join its opposition along with other likeminded intellectuals and created one of the first anti-fascist clandestine movements – "L'italia Libera" .The manifesto highlights the potential of the intellectual developments made by the different prisoners, who may have had opposing political backgrounds, while being punished for similar reasons.

First-Hand Accounts

Alberto Jacometti provides some vivid first-hand accounts of the landscape of the exile quarters and general conditions on Ventotene. Jacometti spent a great deal of time recounting his experience on Ventotene in the finest details. He describes the general landscape and the women's quarters:

”While here and there someone is seriously taking care of the canteens, the library, one of his tiny workshops, the others idle chat from morning to night. Either they stretch out in the sun or, sitting in the air and pinafore - and perhaps naked to the waist - they talk imitating the schoolchildren who learn a lesson. The observer - if he remembers above all that there is war elsewhere - will end up concluding that he is in sight of a colony of madmen. Let's leave him with his impression and proceed on our behalf. It's summer. We enter the border town five minutes before six. We went down a ladder with very large hailstones and we find ourselves on a vast square in cement, deserted. On the right, we meet the first pavilion/tents: it is a little smaller than the others; the women's pavilion. It's closed. At the end of the square, on the left, there is a large brick staircase: let's climb it. In front of us we will have a second large terrace with, in the middle, two flower beds cultivated with vegetables and, in the background, a few rows of large rooms. Each bedroom up here is made up of a two-seater bedroom and two bedrooms containing twenty-five camp beds each, it starts with an atrium and ends with washbasins and toilets. There are therefore 52 x 7 = 364 confined. In recent times the camp beds in each dormitory have risen to 27 and the total number of confined to 378”.

He also describes the nurse station and its handling of tuberculosis:

”The terrace is closed on the right by a boundary wall which supports the guardhouse. We go back down the stairs a little while ago and turn to the left side of the women's room. On the left, another staircase, shorter, at the top of which is another terrace. It is the most beautiful. There are three large central flower beds, one of which, the first, the confined ones [those exiled] who cultivate it, - they are communists - have transformed it into a small garden. A tiny magnificent garden: full of succulent plants and brightly colored flowers, which follow one another with the seasons and make the flowerbed a continuously changing carpet ... On the left, in five rows, five large bedrooms; here also at the back the boundary wall, on the right, almost plumb-lined on the bend of Calarosana, a little upright, the pavilion/tents of the TB (tuberculosis) and, in a corner, the infirmary 5 x 50 = 250 confined [exiled]; infirmary and TB about forty; in full periods 300 in all. We are at 678. About twenty women, 700”.

The gloomy and unfavourable conditions can be seen in Jacometti's recount:

”And the populace is right, at least in this, that among the many possible corruptions of Pandataria (Ventotene) the one that only made sense prevailed. (He) who wants to shrug (have a bad time), spend(s) the winter in Ventontene.”

A fellow anti-fascist and partisan Giorgio Braccialarghe highlights the impact of Jacometti's work:

”In the afternoon, while Spinelli was taking care of his rabbits, I immersed myself in reading. Almost always a manuscript by Alberto Jacometti, who churned out novels in a continuous stream. The characters he created, or reproduced, were saying intelligent things and saying them well. Perhaps they lived in a world in which an erotic accentuation was reflected, due to the abstinence that the author and all of us had to endure”.

Braccialarghe also describes his living conditions on Ventotene and their implications on his intellectual developments:

”In Ventotene there were a dozen pavilions, all the same, more like hospitals than prisons.... I had the last cot. On my right, I had Pietro Secchia, The Secchia, physically clumsy, with glasses and temples, thin, of good stature, if for the position he held he was to be considered a red cardinal, in reality he was a poor country parish priest. During the day, he looked after a little shop, in which horrible canvases were displayed, which he himself painted. If art is a religion, his works were blasphemies in color. For his party comrades, it was a kind of incarnate verb; for me, an annoying animal that snored and indecently, forbidding me to concentrate my ideas”.

”In Ventotene life flowed monotonously, on the obligatory tracks of regulation. With the ringing of the alarm clock, the screeching of the keys in the locks started the day. The confined, finished dressing and rearranging the cots, rushed to the first roll, then in the morning presented no other obligations...At noon we ate our first meal. A watery soup, often made bitter by the sea water that replaced the unobtainable salt. An absolutely insufficient second course was a few grams of bread. Tease the digestive glands, we went to the second roll. Towards the end of the afternoon the third session and dinner as cheap as lunch. In the evening, after the last roll call, we returned to the pavilions, the doors of which were locked. So, for months and years. Surrounded by a sea that gave wishes for the infinite.”

Another snippet of life in confinement is told by Ernesto Rossi wherein he describes that many confined, to kill time, decide to put on a small orchestra despite their inability to play. In a letter to his mother dated January 19, 1941, Rossi expresses, with the ironic and pungent style that suits him, his disappointment with those he defines as the "music addicts" of confinement:

”It's four o'clock. As soon as four o'clock strikes, the clarinet attacks. He is a confined person who learns, in a large room in front of ours. His companions have managed to impose limits on time - from 4 to 5.30 pm - and on space: he has to study in the latrine. But within those limits he unleashes his passion to the maximum. He's been studying for six months now, and he still can't make the ladder. If he is lucky enough to spend another ten years in confinement, perhaps he will come to play the first few bars of "Goodbye, my beautiful goodbye ..." He has found the best method to make himself loved. There are at least a hundred-confined people who would gladly break the clarinet on their heads ... Here, in our small room, we are lucky. In a big room, there are two accordions - one for wind and one for bellows - then guitars, mandolins, violins, gramophones ... Music addicts and drunkards are the plague of confinement

Rossi frequently wrote to his mother and wife offering an exhaustive picture of the confinement conditions during his years in exile. He complains, for example, of the presence of insects, or the progressive lack of food starting from 194. His mother and wife often ask for clothes and food, but above all, it was always his concern to solicit the sending of books, constantly informing them on the progress of their studies and projects. There was however, a barrier to honest conversation. It was not possible to freely express everything that happened on the island, because the letters were still subjected to the watchful eye of the censors:

”If I could tell you the stories, the gossip, the messes, the scandals of the confinement, I would not miss topics to fill the pages, telling you about our life, but like this ... Even when I was in jail the same happened: of the things that I do. directly interested, even if funny, I could never write to you.”

From the recounts of the ex-exiles, we can see a clear shift in the issues and everyday workings of confinements on this island. There is still the evident lower quality of life made available for the prisoners; however, we see here a clear joining of intellectual forces that continued to fight against the fascist state. There was a strong effort to maintain the education and intellectual developments on Ventotene with the major forms of punishment being restrictions placed on what books and what kind of teachings and intellectual discussion could take place.

Contemporary views

Today, Ventotene is largely sought after for its natural beauty and is mainly visited by tourists for recreational purposes. In conjunction with the Island of Santo Stefano, Ventotene is a nature reserve and a Marine Protected Area

The references to Ventotene's exile past appear to be largely lacking compared to the other Italian ex-exile islands in this paper. Many tourist websites fail to mention this part of the island's history and for those that do, there is only a brief mention. There is a greater mention of the Roman Imperial era of exile than there is that of the twentieth century. Neither of the two museums on the island, the Migration museum and Ornithological Observatory and Archaeological Museum, mention the island's period of exile.