IKARIA

Location and Topography

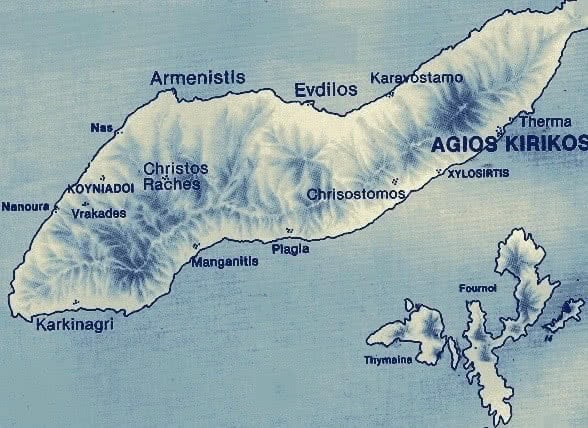

Ikaria is situated in the Sporades island chain and lies in the north-western Aegean Sea, near the Turkish coast. Ikaria's uniquely positioned geography paired with annual winds or meltimi make its waters the most turbulent and treacherous in the Aegean.

The island's coastline is “unbroken”, with no natural harbours or gulfs protected from the strong Aegean winds. Only 5% of the island's mass is arable farmland. The island is subject to strange wind patterns (the aforementioned meltimi) which cause damage and feed wildfires. The island infrastructure was not improved until the 1950s, when local Ikarians and those who had moved to abroad began to invest in their homeland.

Locals would contribute time and manpower, working for a few days free of charge every year to build suitable roads for cars, and the Ikarian diaspora would send funds through the Pan-Ikarian Brotherhood to invest in schools, libraries and general improvements. In the 1980s, the Greek government constructed a sea wall to shelter incoming ships, providing safer passage to and from the island, making transportation to the island much less perilous.

Exile Era

Ikaria's use as an exile island began in the Roman era originally, with the hot springs at Therma providing a comfortable yet remote prison for wealthy political opponents of the ruling elite. The Byzantine Emperor exploited Ikaria in a similar fashion; a tradition spanning centuries and political state authorities.The twentieth century reestablishment of exile or “administrative banishment” on Ikaria began with Prime Minister Venizelos in the 1920s, and increased drastically under General Metaxas's dictatorship and his systematic exile of political opponents in 1936.

Metaxas deported royalists, remaining loyal supporters of Venizelos, politicians, and leftists; approximately 150 of whom were sent straight to Ikaria. Because of the inhabitants' suspected leftist sympathies, the island was supported little by the Greek government and largely felt ignored by various State authorities, contributing to its independent spirit and lack of obedient conformity. Ikaria did not exist in the eyes of the occasional Greek government as anything else other that as a place of exile as the island was viewed as hopelessly leftist. It was even dubbed the ‘Red Rock' for its assumed Communist sympathies. Continuing into the next several decades, in 1946, after the end of the Second World War and the subsequent beginning of the Greek Civil War, the Tsaldaris government exiled a group of leftist leaders from the EAM (Greek Liberation Front) and ELAS (Greek Liberation Army) to many exile islands, one of which was Ikaria.

Over the 1946-1949 period, “wave-after-wave” of exiles arrived, with an estimated total of thirteen thousand being deported over the three years and thirty thousand passing through the island in total. The practice of exiling political opponents finally fell out of favour with N. Plasteras' government in 1950.

Punishments

While Ikaria was one of the milder islands in terms of organised punishment, no additional infrastructure spending was allocated by the government. The prisoners were only provisioned ten drachmas (approximately $0.30) daily for their upkeep, with rations of dried bread and beans or lentils. There was no additional clothing or accommodation allowance, no new housing or medical centres built, and the pleas of the islanders for additional resources fell on unsympathetic ears. One minister is claimed to have said that he would sooner bomb Ikaria with exiles and residents alike rather than provide further financial assistance.

The islanders, though impoverished themselves, banded together to find food and clothing for the prisoners, and allowed them to live in abandoned houses or barns or as lodgers in their own homes. Restrictions such as curfews, unannounced household searches, and beatings were frequented on the locals and prisoners alike by the island gendarmes for the smallest infringements. They would often be terrorised in an effort to make them sign a dilosis statement denying Communist ideas and their comrades. While this was successful in other parts of Greece, on Ikaria it was treated as a denial of oneself, one's brothers, and their political beliefs, and was therefore treated with the highest distain.

Tuberculosis became rife on the island, and the exiled doctor Dimitris Dalianis initiated help for those in need at the Sanatorium designated for the sick, as no other medical aid was provided. The community spirit and danger that the medical volunteers placed themselves in was quite extraordinary, as they were exposing themselves not only to the disease, but also harsh punishments if discovered; as they falsely diagnosed fellow detainees with medical training to assist in the operation, without the knowledge or permission of authorities.

Figures of Note

- General Napoleon Solitis; war hero of the Balkan War, exiles by Venizelos in 1923.

- George Mylonas; leader of the Agrarian Party of Greece, and political opponent of Metaxas, exiled in 1936.

- Miki Theodorakis; exile in 1947 and again 1948, later became a famous composer.

- General Stefanos Sarafis; head of wartime ELAS, held in 1946.

- General Bakirtzis; EAM officer.

- Dimitris Partsalidis; EAM secretary and later prime minister, who escaped the island in 1947.

- Andreas Tzimas; KKE, fellow escapee.

Life with the Locals

The locals were treated as collaborators and often deprived of their civil liberties. Ikaria was distinct [from other exile islands] in that it involved a particularly close and intensive form of cohabitation of local and exile communities, which included the exchange of lectures and education, as well as physical labour by the exiles, in exchange for the “philotimoi” (or patronage) of the islanders. The islanders of Ikaria were famed from the nineteenth century onwards for their extreme generosity and accommodating nature to guests; Ikaria was a society without a state for long periods of time, and thus its members developed relations of solidarity and reciprocity. It seems the same national neglect that dictated Ikaria's independence and ‘leftist tendencies' also encouraged the sharing and hospitable traits so commented upon by visitors.

The exiles tried their hardest to respond in kind to their new benefactors. The exiles formed the OSPE organisation to dictate a moral code for how to treat their island hosts, which included forbidding fraternisation with female islanders, among other rules. The close communal spirit of all inhabitants of the island was especially prevalent on the Easter celebrations of 1947. The exiles formed a choir to chant in the churches, and confectionary and presents were exchanged between the islanders and the exiles with the few provisions available.

First Hand Accounts

“The most unbearable thing was, of course, that I was not free and at any given moment there was a shadow of fear for the day to come. Nonetheless, when I think of Icaria, a wave of light washed over me … the beauty of the island in combination with the warmth of the locals. They risked their lives to be generous to us, something that helped us more than anything near the burden of this hardship. Showing no fear to our wardens, then opened their houses and their hearts to us … They treated us like brothers…” - Mikis Theodorakis, 2003, in The Album of the Festival of Ikaria.

“We couldn't believe that apart from the many leftists on the island, many of our hosts were ardent rightists and royalists and they were offering us their houses to stay in and their few products to eat. It is thrilling even after so many years to think about that”. - Kostas, former exile, 87-year-old.

“We were treated as exiles even when we did not have exiles to live with us. We learnt how to organize our lives, how to survive and above all how to resist each time greedy invaders, call them pirates, Turks or Athenian politicians, who only wanted to take our few belongings away and our children as soldiers. We got to know how to hide and help each other and that's what we also did when living with the exiles”. - Kostas from Arethousa, 86-year-old

Contemporary Views and Changing Values

Today, Ikaria is famous for other reasons. In 2012 the island was declared as one of the world's Blue Zones, for the unusual longevity of the locals living there. One in three islanders is said to live passed the age of ninety.Ikaria is also now famous for the extravagant overnight summertime Orthodox festivals, known as panigyria, comprised of dancing, food, and live music.