ITALY

When we look at Italy’s history, we can become perplexed in the fact that the nation has a long past, but a short history. The modern Italian state was born between 1865-1870 and when looking at Italian Fascism we can see that there is over a century of Italian history that was not Fascist. The dark curtain that Fascism cast over Italy however brought with it consequences that have become cemented into Italian memory.

In the early 20th Century and post First World War era, Italy experienced a whirlwind of economic and social hardships that eventually ignited revolts, forcing the declaration of military intervention. It was common for Italians to escape this chaos and between 1870-1910 over ten million people left Italy for countries like the USA and Western Europe. In the midst of the unsettled state, it was no surprise that a charismatic leader offered hope to those that had been severely affected by the circumstances of their surroundings. Gifted with oratorical skills and an uncanny ability to assess the political climate, Benito Mussolini became a key figure in the Fascist Party from its origins in 1919 to his assumption of national political power. After accepting the position of Prime Minister by King Victor Emmanuel III in 1922, Mussolini went against Italy’s constitution and centralised his own authority; by 1925 Mussolini had assumed a total dictatorship

Fascism promised to create (or recreate) a specific type of Italy that to be was built upon a particular and effective strategy. The first of which was that the country was to be unified around a common party ideology and Italy: Mussolini. The second was the promise that Italy would have their prestigious place in the world again, recalling the glory of its Ancient Roman heritage. Thirdly, the divisive problem of class struggle was promised to be replaced by inter-class unity. And finally, the historic breach with the church, which had marked the first sixty years of the Italian nation, was to be restored through the Lateran Pacts of 1929. Individuals related to this in different ways, with many supporting the regime while others openly rebelled from exile or within Italy.

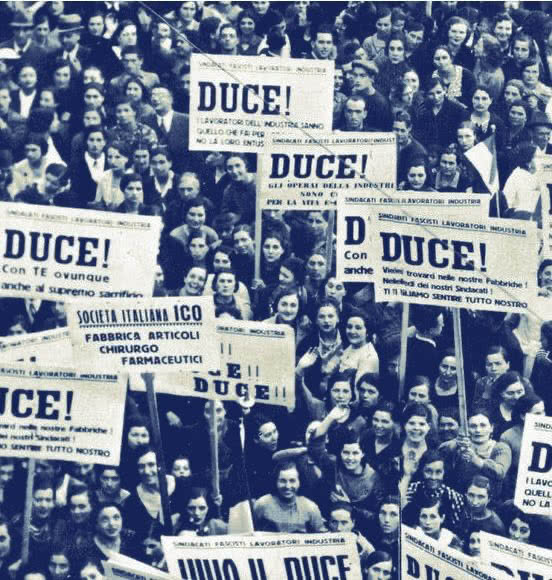

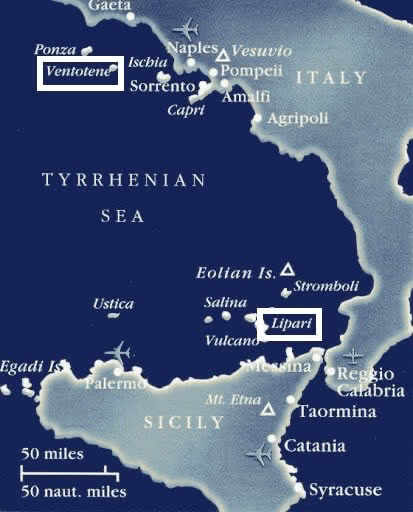

For many Italians, the regime’s achievements seemed plausible; social peace at home and respect abroad were palatable to politically conscious Italians previously accustomed to social uncertainty and international humiliation . Mussolini acquired an almost divine status in Italy, and was variously portrayed as the 'new Caesar', a great statesman and military leader, a strong athlete, and a figure helping the peasants with their harvests. Likening his divine leadership to the that of the Ancient Romans, Mussolini also revived the archaic practice of banishing those who did not fit his regime: the practice of island exile.

Although never united enough to enact collective action, the anti-Fascists were predominantly able to develop and strengthen their movement while in international exile, prison and/or internal exile. The implementation of exile, or confino, occurred in 1926, when the Chamber of Deputies and The Senate promulgated the consolidated bill Testo Unico delle leggi pubblica sicurezza (TULPS: consolidated acts on public security), revealing the brutal efficiency with which the regime defined and deprived citizens of their rights. Places of exile, in some instances acted as both political and military schools of anti-Fascism and this was particularly true for the working lass, who, while 'free', would not have come into contact with either the teachers or rhetoric of the anti Fascist movement.