GREECE

Early 20th Century Greece was a country in constant political upheaval. Eleftherios Venizelos (Prime Minister 1910-15, 1917-20, 1924, 1928-32, 1933) and General Ioannis Metaxas (Prime Minister 1936-1941) both practiced the exile of political opponents to remote islands in Greece. Venizelos passed a law in 1929 to allow the imprisonment or expulsion of anyone with the means or intention for the “overthrow of the established social order by violent means or the detachment of part from the whole country”, mostly spurred by the growing unease in Europe caused by the Bolshevik revolution. Metaxas’ dictatorship was far stricter in its approach, and brought in the template of reformation in 1938 which would last throughout the coming years; to declare repentance against Communist convictions, to establish concentration camps as an alternative to this, and to create the 'loyalty certificate’ for governmental inspection for anyone hoping to work in the public sector.

During the Second World War, the National Liberation Front (EAM) and their military counterparts ELAS were leaders in the resistance against the Nazis. They were backed by the KKE, the Communist Party of Greece, fighting alongside the Allies. When the war ended in 1945, the Varkiza Agreement was signed by the EAM and the Greek government, but the foreign-backed right-wing state soon turned on the left, and soon the country was plunged into conflict. The Civil War (1946-1949) resulted in tens of thousands more Greek citizens being internally deported en masse to dozens of islands. In Greece alone, there were forty-three islands used for political exile and internment camps. For Greece, not only the political conditions but also the geographical distribution of the country, with hundreds of islands, was essential for conceiving and realising the practice of political punishment and exclusion. The remainder of the 1940s resulted in potentially hundreds of thousands of civilians and military servicemen being exiled or imprisoned across the islands. This included active Communists, ELAS guerrilla fighters, those holding leftist views or sympathies, supporting friends or family members with these views, or being associated in any way with leftist political organisations and gatherings.

The legal and justice systems involved in approving this could not be relied upon for their integrity. Public security committees declared exile status for those on trial, although in this case 'on trial’ is just a figure of speech, with no official courts and often no criminal charges being brought against the prisoners. Originally set to be a year long term for exile without charge, this was later extended to 24 months with absolutely no convictions of legal wrongdoing. Leftist sympathies were the only requirement by civil authorities to banish men, women and children for months to years, splitting up families, and imposing harsh living conditions, poor rations, and in most cases a complete lack of infrastructure to support the sudden influx of newcomers to the islands. The system continued for years, with little official ruling over who was considered an enemy of the state, and therefore suitable for internal exile, other than reports by the secret police who legalised political persecution retroactively.

Over several decades and various political regimes, dozens of different islands were used to isolate, discredit and re-indoctrinate thousands of their own citizens for being politically opposed to the state. The Tolstoy Conference of 1944, and the resulting ‘Percentages Agreement’ between the British, United States, and Soviet leaders, dictated the level of influence approved by each nation over Europe after the end of the Second World War. This surreptitious pact resulted in the European countries being divided between the Western (Capitalist) and Eastern (Communist) powers by the leaders of the three nations, with little to no say by Eastern and Central Europe in their own democratic futures. It would, however, be remiss to say that exile as a form of political suppression in Greece began here. This is a tradition that went back to Rome and antiquity.

Depending on the island, the political regime, and to which level the political detainees were unrepentant, the experiences on these islands could vary vastly. Methods elsewhere were more violent and deadly. On Makronissos, the only military detention camp of the exile islands, Vardis Vardinogiannis described his fellow exiles being stripped of their clothing in winter, thrown into the sea, and then beaten unconscious. Yaros exiles were described as being treated to a gruesome educational holiday, with torture and violence permeating the narrative of the island in a running history of internal strife, civil war, and fratricidal histories. On Leros, children were sent to a re-education and reformation centre known as the Royal Technical School. The former Fascist Italian Naval barracks at Lakki were converted to host the heavily propaganda laden school, which became one of the largest and longest running such institutions in Greece. Officially the Technical School pupils were orphans, but often the truth was that they had been separated from their leftist families who were imprisoned or on the exile islands, or their parents had been declared “dead” by the state Queen’s Fund.

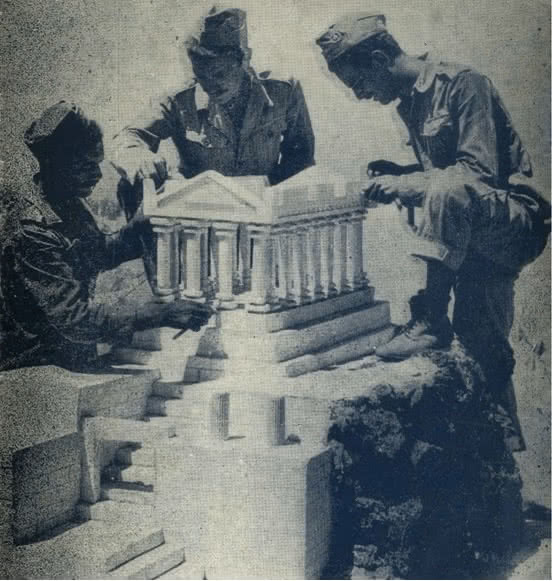

The intention of the Greek exile islands was not only to isolate the Communist element, so as not to corrupt the mind and the soul of the rest of the population, or other prisoners, but also to reindoctrinate them in the patriotic ideals of the true Greek state, stretching back to antiquity. It was this classical Nationalistic imperative that inspired the Greek government of 1946-1949 to allow the detainees to illustrate their imminent redemption by reconstructing classical structures and monuments on Makronissos, such as the Parthenon, as a way to show their patriotic rehabilitation.

In 1950, Nikolaos Plastiras’ cabinet attempted to broker a peace between the left and right, brandishing the slogan forgetfulness and amnesty. Martial law was lifted and several extreme measures in use up until this point were relaxed. Many of the exiles were released, death sentences were commuted and there was a general impression that tensions were easing. In actual fact, the Cold War allowed the right-wing to maintain an anti-communist rhetoric through this period, with apochromatismos (decolouring) declarations, delegalisation of the KKE, and paid informants supporting the continuation of democratic suppression until at least 1963. A renewed political suppression and exile to the islands, this time of all parties and political leanings, came with the Colonels’ military Junta of 1967-1974. It was the Junta’s disastrous involvement in the Cyprus conflict that finally united the whole Greek nation against internal divisions and state sanctioned violence, and ended the political animosity resulting in internment and exile as a means to control.