MAKRONISOS

Location and Topography

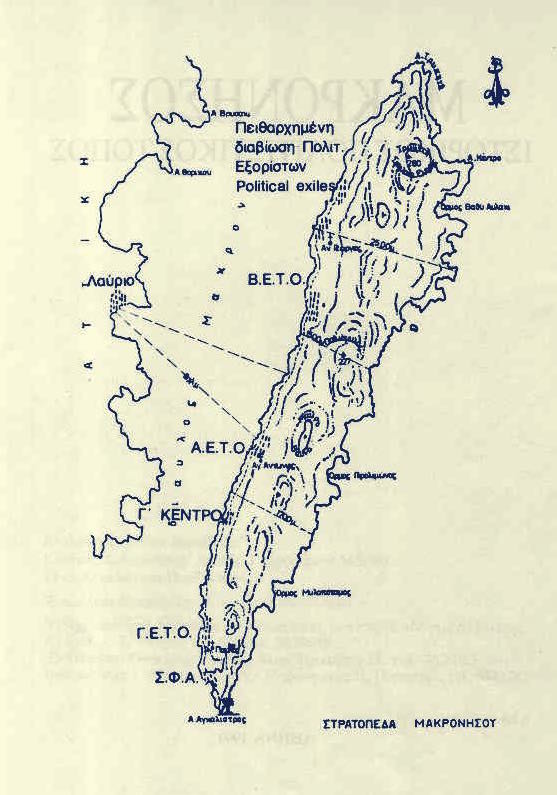

Makronisos is a completely barren, 13km arid rock, still uninhabited to this day. It lies very close to the coast of Attica, near Lavrio, and has a long, thin shape, lending the island its name from 'makris' meaning 'long' in Greek. The rough seas and strong winds surrounding the coast suggest ideal topography for exile and exclusion from the general population, while still being close enough to access on a regular basis.

Exile History

With the onset of the Greek Civil War, the right-wing government used conscripts to fight the leftist Democratic Army of Greece (DSE). Many of the conscripts had leftist sympathies, however, or had supported the EAM during WWII, so this dichotomy needed to be addressed. The Makronisos camp was the solution. Exile to the military penitentiary on the island began in 1946, and increased dramatically with the Greek government's 'Resolution 73' of 1949, aimed at the reformation and rehabilitation of leftist sympathisers, now including regular civilians, back to the ideals of ethnikofrosyni (the nationalistic right-wing ideals of Greece). The military remained the ruling presence even when the Organisation of Corrective Institutions of Makronisos (OAM) followed them as official administrators, even with the introduction of civilians to the island, which reflected the increasing influence of the army in Greek society.

From this point onwards, nearly all male political exiles were sent to Makronisos as a way to rehabilitate them, and from 1950 female prisoners were also sent here, though to a different camp. Ethnic and religious outsiders were also dealt with by being banished to the island. The general estimate is near 50,000 individuals being incarcerated on the island over these years, though no official records remain.

Punishments

The method of re-education in most cases was hard labour, strict discipline, torture, and anti-communist propaganda. The soldiers were terrorised and beaten, using billy clubs, crowbars, whips and steel wire or their bones broken in an attempt to get them to repent and sign a declaration renouncing Communism. They were also forced to stand one legged for extended periods of time, beaten on the soles of their feet, or hung from poles with their arms tied and having to stand on tip-toe. The unrepentant were forced to carry out manual labour, in between the beatings, or unnecessary tasks, like moving large heavy rocks with no purpose. They were disoriented and sleepless from night raids on their tents, and sent to isolation areas surrounded by barbed wire fences where they were not fed and provided little water. There was a strong implication that to be Communist was to be not only un-nationalistic, unpatriotic, but also therefore un-Greek. The unrepentant leftists were called 'Slavs' or 'Bulgarians', constantly interrogated and tormented.

There were even murders by the military police. In 1948, over two days, Makronissos army officials purged the island of dissidents, who had argued with soldiers but were unarmed when gunned down. The exact number of individuals killed in this event are still under debate, as no official records were kept, and it is believed the bodies were thrown into the sea as a means to cover up evidence. Estimated figures range between fifty and three-hundred-and-fifty prisoners killed at this one event. This unjustified killing inspired such fear in newcomers to the island that they would often sign their repentance papers on the way there. This constant barrage of fear, physical and psychological abuse began to convert waves of detainees, the rehabilitated soldiers were then required to operate an ability and willingness to engage in the torture and terrorism of fellow detainees. There was the intention by the island’s military administration to divide and conquer, to create an obvious distinction between one side and the other by making the repentant complicit in the punishment of their former comrades. Those who had signed would be expected to make speeches and read declarations against the KKE in front of the other detainees, as well as writing letters to their villages renouncing their former ideologies.

The site ran as an internment camp until the fall of the Junta in 1974, with an estimated 50,000 inmates in total. The island has been protected by the Greek state since 1989, and was recently declared an archaeological site.

First Hand Accounts

Never yet have I been tried or been sent to trial for violating any law, and I have no criminal record whatsoever. - Antonia Flountzis, doctor, in exile or prison for 24 years. Modern Greek Archives/League for Democracy in Greece Archives, Info XI, individual dossiers, letter from Antonis Flountzis from Tripolis, Greece, 3 July

Makronissos was so barren and uninhabitable that Ikaria seemed like a heaven in comparison -Sofia, local Ikarian.

When I arrived at Makronisos I was stunned; I understood that I am Greek and I saw with my own eyes the lies that the comrades were saying to me. My blood heated up and I immediately came to my senses when I saw “The Parthenon,” and, carved upon the rocks with big letters, “Now above all the struggle”, “The feats of our ancestors lead us,” “Hellas is an ideal, that is why it does not die,” “In the mists of the centuries, the Parthenons will remain grand symbols, to enlighten, and to remind of their glory for ever - Skapanefs 11 (1948)

A story that I will tell you is the story of thousands of the people’s/nation’s children, thousands of fighters of the national resistance, who for their democratic views were disarmed, imprisoned, beaten, inhumanely, sent to Hitler like design of Makronissos, literally martyred. This is how the ELAStis Makronisiotis began his story - G. Tzopas, a wounded soldier of the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE), on his stint at Makronissos.

Summer. The hot sun melts the iron. The dry land of Makronisi makes me feel like it is burning all over. Nowhere shadow, Nowhere water. And in the middle of the day hundreds of Soldiers climb the top of the island in the morning, carrying on their backs a huge boulder. And back the executioners curse them and hit them. They arrive in a daze, overwhelmed at the top. They climbed the horrible Golgotha, sit or rather throw themselves on the ground to rest. But their executioners start kicking them. March forward. Get up, owls, dishonorable Bulgarians. And they go down, and they go up again. and their horrible torment continues for days and months. - G. Tzopas

The painful days of Macronisos were followed by nightmares, martyrdom nights. As soon as it got dark, the heartbeat started. Whose turn is it tonight? We do not take any night without hearing the wild groans, the tearful voices of pain from a colleague, to your competitor [guard] who is inhuman. - G. Tzopas

On October 3, it was my turn. My own testimony began. I was beaten 34 times from eight at night until 12 midnight, I fainted 5 times. They let me go. But my sufferings werenot over. I was hit just as hard on November 9th. I made it through. They let me go. But again, the executioners did not leave. I became familiar again to this on December 15. I was literally crushed into the wood. I made it through this time too - G. Tzopas

Contemporary Views

The island of Makronissos is now completely uninhabited, left to its past and left to nature. In 1989, the Greek Ministry of Culture declared the island as a civil war historic place and monument, prohibiting demolishment, construction, or intervention for the surviving buildings, as an archaeological site. In spite of this, there is very little acknowledgement from the state of the atrocities committed here, with most commemoration of the events being recorded in the Makronisos Political Exile Museum in Athens, and the Ai Stratis Museum of Political Exile, also in Athens. There have been calls in recent years for further recognition of the painful history of this place, in a similar fashion to the concentration camps of Nazi Poland and Germany, telling the full story if for no other reason so that they will never be repeated. There have, however, been additions of monuments erected on the island by interested organisations independent of the Greek state, most recently by the Communist Party of Greece in September 2020. So many of the documents and evidence from at the detention camp were destroyed in the 1980s.

There is little access to the island now, with no current ferry routes or island-hopping tours docking at the island. The recent official state interest in the island has had most focus on its maritime archaeology, due to the discovery of five ancient shipwrecks dating back to the mid-Hellenistic and the post-Roman era.